|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| In October 2009, family and friends traveled across the border to celebrate the wedding of my sister Susan and her husband-to-be, Michael. I think we'd all agree -- our visit to San Miguel was not long enough! This historical Mexican town is truly spectacular, and I felt it deserved its own special page in this journal of our trip. |

|

|

|

Una Ciudad Muy Vieja |

|

|

|

Known for its pleasant climate, charm, and Old World flavor, beautiful San Miguel de Allende is a step back in time. While there are, of course, modern conveniences throughout the colorful town, its cobblestone roads, historic colonial buildings, and traditional culture are much the same as they were hundreds of years ago. Because San Miguel is so quaint and tranquil, it might be surprising to some visitors that San Miguel's population is close to 150,000. Less of a surprise is that about 10,000 of those people are expats, people from other countries, primarily from the U.S. The lure of the beautiful old town is strong.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Click above image for more photos. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| El Oratorio de San Felipe Neri |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| La historia de San Miguel de Allende |

|

|

| San Miguel de Allende resides in the state of Guanajuato in a relatively flat part, the Bajio, of a mountainous area of central Mexico. Before the arrival of the Spaniards in the 1500s, the area was home to local Indians, the Chichimecas. They were nomadic hunters, and they resisted Spanish invasion. In fact, it is with pride that locals today claim that the Chichimecas of the area were never truly conquered by the Spanish conquistadores. Because the Chichimecas were nomadic groups and not an agricultural civilization, they were difficult to find, and they could sneak in at night and attack the Spanish and then disappear just as quickly. But though they might not have been conquered by los conquistadores, they can't boast the same about resisting the religious influence of the Spanish, and religion has become a very deeply integrated part of their culture. |

|

|

|

|

In 1542 a Franciscan monk, Fray Juan de San Miguel, traveled north through central Mexico. He established a mission there to convert and support the Chichimecas. The original site of the mission, known as San Miguel el Viejo, was attacked by Chichimecas, so the mission was moved to its existing location by a spring, El Chorro. And over time, the Chichimecas converted to Catholicism. The village became a town and later an important stop on the silver route, the Antiguo Camino Real, along which the Spanish transported silver from Zacatecas to Veracruz. The town then became known as San Miguel el Grande

In 1779, Ignacio Allende was born in San Miguel. Though born to privilege, he became a conspirator against the Napoleonic regime in Spain. He was a major leader in the early Mexican war for independence, though a traitor's betrayal led to Allende's capture and beheading. For General Allende's heroic role in the rebellion, San Miguel el Grande became permanently renamed San Miguel de Allende. Casa Allende, the birth home of the revolutionary hero, is now a museum, the Museo Casa de Ignacio Allende.

|

|

|

|

|

| An interesting historic note to the beginning of the rebellion is the story of the heroine Josefa Ortiz de Domínguez, who aided conspirators in the rebellion. She lived with her husband in the town of Querétaro and was sympathetic to the poorly treated American Indians, mestizos, and creoles. Unbeknownst to her husband, Josefa set up secret meetings in their house for rebel leaders, including Father Miguel Hidalgo and Ignacio Allende, to plan the revolution. She also gave financial aid to the revolution. When someone betrayed the conspirators, Josefa’s husband discovered her involvement and imprisoned her in her room, but she was able to get word to the town’s mayor, Don Ignacio Pérez, who then got word to Ignacio Allende and Father Miguel Hidalgo that the conspiracy had been discovered. Ignacio Pérez is considered the Paul Revere of Mexico. And two days later, just before midnight on September 15, 1810, Hidalgo rang the church bells and gave his famous Grito de Dolores, calling Mexican patriots to revolution a month earlier than originally planned. Mexico officially became independent in 1821. And every year on September 15-16, El Grito is reenacted as part of the celebrations of independence. Another side note: Josefa had either 12 or 14 children, depending on the source you read. A woman with that many children certainly must be brave and tough, as Josefa was known to be. |

|

|

En la ciudad |

|

|

| It's hard to resist the Old World charm of San Miguel de Allende. The cobblestone streets in the center of town are lined with colorful buildings in varying states of disrepair. Partly this is due to materials used, but the unfinished or older look is usually kept on purpose. In many cases, a drab exterior actually opens up to a beautiful plant-filled courtyard. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Some of the streets are so narrow that big vehicles cannot navigate through them -- drivers who park their cars along the curb are very careful to fold in their sideview mirrors. But that doesn't keep tour buses and circus caravans from moving along the largest streets. |

|

| Outstanding craftsmanship is visible throughout town. Ornate hand-carved doors, unusual door knockers, and exquisitely carved balconies, often in contrast to the rougher building they adorn, capture the eyes of passersby. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Boutiques and shops filled with art, clothing, rugs and other textiles, and pottery line the streets in the center of town. For less pricey options, many people prefer to visit the stalls of local artisans in El Mercado. Vendors and stores keep interesting hours -- you never know which ones will be open when, which makes each walk through town an interesting experience. One clothing boutique even housed a dentist during our visit.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

La Casa del Mayorazgo del Canal was a beautiful colonial mansion and home to one of the most famous and wealthy families of San Miguel, the Canal family. Today it houses the Banamex Bank, but the beauty of the architecture and elaborately carved door remain.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The netting is there to prevent pigeons from resting among the columns and stonework, but it has lifted away from the building and now the pigeons enjoy the protection afforded by the netting. As a matter of interest, the country home of the Canal family today houses the language and art school Instituto Allende, and the convent built by one of the Canal daughters is now home to the Centro Cultural “El Nigromante,” Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes in San Miguel. |

|

|

|

|

|

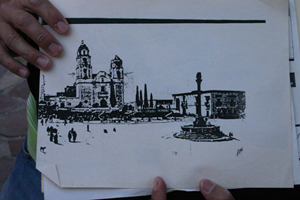

| Adjacent to the famous Canal house, El Jardin is the central gathering spot for the people of San Miguel. Groomed laurels provide shade, and wrought-iron benches surround the garden. There, people rest and visit, listen to music, or read newspapers. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| La Parroquia |

|

|

|

|

Towering above El Jardin is La Parroquia de San Miguel Arcángel, a majestic church and a symbol of Mexico. A statue of the Franciscan monk and the town's namesake, Fray Juan de San Miguel, is displayed outside the church.Though the Parroquia's Gothic look makes it less traditional in appearance than the rest of the town, there is great history to its creation. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Long ago, the church, of course, was much simpler. And Franciscan monks held services outside for the Indians who preferred not to enter the church building. |

|

|

|

|

The original Parroquia was built in the 1600s. Then in the early 18th century, a multi-towered, somewhat Gothic façade was built over the front of the church at the request of the first Mexican-born bishop. What is fascinating is that the façade was designed by Zeferino Gutiérrez, a skilled but illiterate stone mason with no formal training as an architect. His design was based on postcards he saw of true Gothic cathedrals. Supposedly when he instructed the workers each day, he drew pictures in the dirt to show them what to build next. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The Parroquia has become a San Miguel icon and, though odd in its history and color, is beloved by Mexicans across the country. From the pictures I've seen, the cathedral is spectacular at night as well, quite dramatically lit. |

|

|

|

|

|

During festivals and other celebrations, tall decorations called xuchiles are erected at the Parroquia. These platforms, part of a pre-Hispanic tradition, are made with bamboo-like strips and woven pieces of cucharilla, or "little spoon cactus" (also known as frayed sotol and green desert spoon). They are decorated with juniper and cempazuchitl, or marigolds, woven into place with stems. The cempazuchitl are symbolic of death and are also used in Días de Los Muertos activities.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| These xuchiles were carried to the Parroquia in a parade for La Alborada, a festival for the patron saint San Miguel. They remained at the Parroquia for many days after the festival's end. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| This detail on the door shows Michael the archangel, patron saint of San Miguel. |

|

| The interior of the church is truly a sight to behold. The simple brick and stone masonry seems a contrast to the complexity of the arched ceilings, chandeliers, and gold-painted features, but it all works together, and I think I prefer this cathedral to any of the fancy European ones I've seen. Other arched brick ceilings can be seen elsewhere around town, and they are some of my favorites of Mexican architectural elements. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Inside the church to the left is a statue of el Señor de la Conquesta, Christ, with two monk statues on either side. According to history, the two monks were killed by Chichimecas as they carried the cross to San Miguel. This violent scene is shown on a mural in another part of the church, seen below. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Near the cross, another mural depicts the Last Supper. Though the faces appear somewhat Asian, the artist was actually depicting the disciples as Indians. Apparently he also included a self-portrait in the image. |

|

| Below the Parroquia is the crypt. It has its own history and interesting design, and it houses the remains of many people, including the former Mexican president, General Anastasio Bustamante. It is primarily opened for Los Días de los Muertos and was closed during our visit. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| This statue is of San Roque (St. Roche), the plague fighter -- supposedly he worked tirelessly to help those who fell victim to the plague in Europe. His legs show the plague sores he endured after contracting the disease himself. The dog beside him holds a bolillo in his mouth, and acccording to religious tradition, the dog brought bread to St. Roche after he was sent away from town. |

|

|

Religion is immersed throughout San Miguel. There are numerous churches in and around town. There are altars to Our Lady Guadalupe (the Virgin Mary) or Arcángel San Miguel everywhere, even in alcoves of buildings and in place of vendor spots in the market. Out in the countryside, one can see rustic altars and small open-air churches, as well.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

And the bells -- oh the bells. Their sound carries throughout town, and they are rung at seemingly odd times throughout the day, into the night, and in the wee hours of the morning. Bells awaken sleepy townfolk to warn them that mass is approaching, that it's really about to start, and that it's starting. And in San Miguel de Allende, it seems as though there is always a festival going on. Nonstop bells let the town know what is happening with the festival, even at 6 in the morning, and fireworks and mariachi bands often accompany the nonstop festival bells -- yes, even at 6 in the morning. |

|

| The historic and beautiful dome of the Templo de las Monjas was designed by the same master stone-mason but untrained architect Zeferino Gutiérrez who designed the Parroquia facade. He modeled the dome after Les Invalides in Paris. |

|

|

|

|

| Adjacent to the temple is the Centro Culturál Ignacio Ramírez “El Nigromante,” La Escuela de las Bellas Artes, a school of the arts that was once a convent. The convent was built for a daughter of the wealthy Canal Family in the mid-1700s when she decided to become a nun. According to local history, during the time of the revolution La Reforma in Mexico, the nuns and priests fled the convent and churches via tunnels to nearby houses, and the military occupied the buildings. Those tunnels apparently still exist and are discovered from time to time by new homeowners. Years later, the convent became the home of the famous art institute (ironically, the convent is now named after an atheist). Inside is some of the most famous art in San Miguel. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Michael the Archangel statue on rooftop |

|

|

| La Tierra y Las Plantas |

|

|

|

|

Driving through the countryside outside of San Miguel, one falls in love with the rugged beauty. The terrain is dotted with prickly pear cactus, mesquite, huisache, and grasses, but sometimes fields of yellow flowers or agave catch the eye. In and around town, the colorful flowers are almost shocking in their spectacular beauty. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Unlike the prickly pear cactus found throughout Texas, the Opuntia in Mexico grow like trees on long padless trunks before opening in an abundance of fruit-covered giant spiny pads, the cactus' height taller than the surrounding mesquite trees. The variety appears to be Opuntia ficus-indica, strictly Mexican in origin. The wonderful cactus trees are also plentiful in ranch gardens. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Agave can also be found throughout the San Miguel area, sometimes growing far taller than a human! |

|

| Although bright orange blooms seen in many of the land's mesquite trees might seem attractive from a distance, the blooms are actually from a kind of mistletoe, Psittacanthus schiedeanus. As with the parasitic mistletoe found in Texas and other areas, the plant will eventually kill its host plant unless severe aid is given. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| What is more mesmerizing? The vibrant colors of the flowers or the spectacular cactus? For me, I'd pick the natural, spiky beauty of the cactus. Flowers are, after all, always beautiful. Give the cactus its due! |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Of course, I even think the black widow spider is beautiful. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|